Epidemic Disease in Colonial Mexico

“…[m]any died of hunger and because no one was able to care for them; in many cases every member of a household fell ill, without a single person left to give even a cup of water to the sick.” – Bernardino de Sahagún

The year 1492 marked the beginning of a period of constant contact and exchange between the Americas, Eurasia, and Africa that continues up to the present. From 1492-1504 at least eighty voyages were made for the Americas, and by the early 1500s nearly all of the Caribbean, as well as parts of Central and South America had been explored by Europeans, mostly Spaniards. After the initial establishment of ports and cities on the Caribbean islands, ship travel between Spain and its new colony became common and regular and with each new ship came various unintended passengers from both Europe and Africa, including rats, fleas, lice, mosquitoes, and a host of infectious diseases carried by the ship’s crew. By 1600, at least twelve epidemics had been documented colonial New Spain.

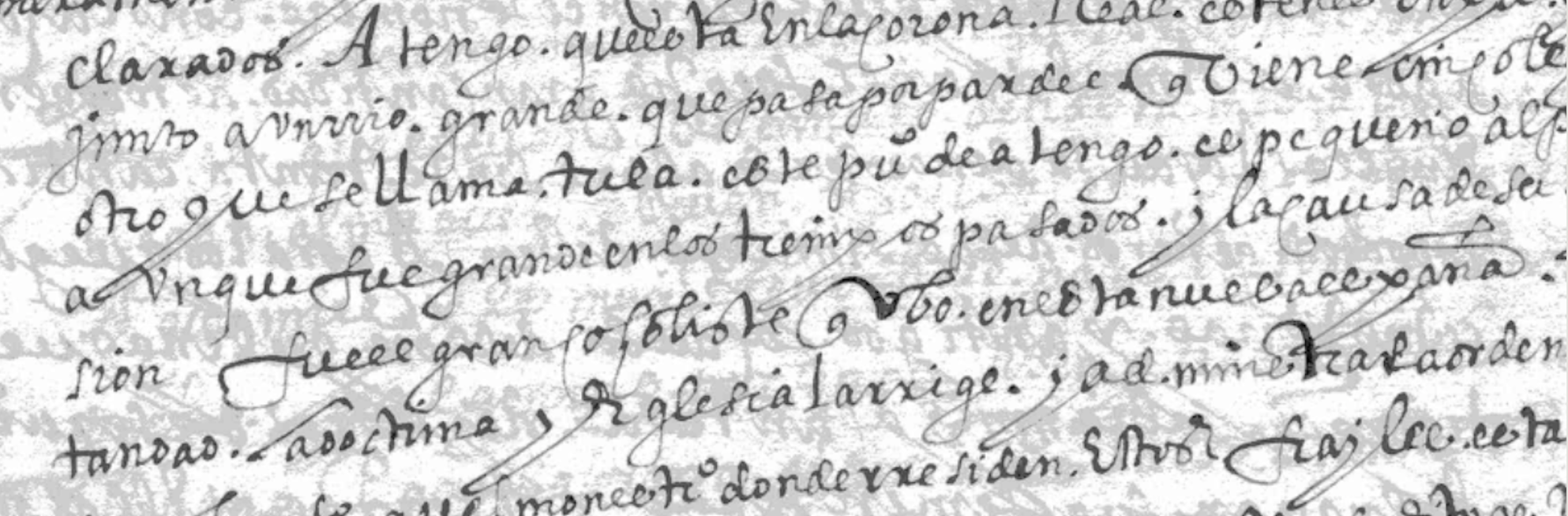

In terms of scale and magnitude, the “cocoliztli” pandemic of 1545-1548 was perhaps the most deadly. Although poorly understood, sources agree that it was “devastating,” with a mortality rate of 60-90% and an estimated 150,000 deaths in the city of Tlaxcala alone. Witnesses, both Spanish and indigenous, did not have a name for the disease, calling it instead pujamiento de sangre (“abundant bleeding,” or “full bloodiness”) or simply representing it pictorially in the form of suffering victims or dead bodies. Descriptions and depictions of the 1545 epidemic appear in more than a dozen early colonial sources and include both Spanish and indigenous accounts, but to date the these accounts have never been systematically analyzed.

In terms of scale and magnitude, the “cocoliztli” pandemic of 1545-1548 was perhaps the most deadly. Although poorly understood, sources agree that it was “devastating,” with a mortality rate of 60-90% and an estimated 150,000 deaths in the city of Tlaxcala alone. Witnesses, both Spanish and indigenous, did not have a name for the disease, calling it instead pujamiento de sangre (“abundant bleeding,” or “full bloodiness”) or simply representing it pictorially in the form of suffering victims or dead bodies. Descriptions and depictions of the 1545 epidemic appear in more than a dozen early colonial sources and include both Spanish and indigenous accounts, but to date the these accounts have never been systematically analyzed.

Recently, we applied high-throughput DNA sequencing techniques to individuals excavated from mass graves associated with the 1545 epidemic at Teposcolula-Yucundaa in the Mixteca Alta of Mexico. Paleogenomics analysis revealed the presence of bacterial DNA from Salmonella enterica Paratyphi C, a pathogen that causes enteric fever.

To better understand this disease and its context, we are now systematically reexamining the documentary evidence for the 1545 cocoliztli outbreak and its relationship to other early colonial epidemics. This research has been funded by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Research and includes work by Harvard College undergraduate students.

For an early view of our preliminary findings, see our historical analysis in the Supplementary materials of Vågene et al. 2018, pages 19-25.

Related Publications

Vågene AJ, Campana MG, Robles García N, Warinner C, Spyrou MA, Andrades Valtueña A, Huson D, Tuross N, Herbig A, Bos KI, Krause J. (2018) Salmonella enterica genomes recovered from victims of a major 16th century epidemic in Mexico. Nature Ecology and Evolution 1-9, doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0446-6.

Warinner C*, Robles García N, Spores R, Tuross N. 2012. Disease, demography, and diet in early colonial New Spain: Investigation of a 16th century Mixtec epidemic cemetery at Teposcolula Yucundaa. 2012. Latin American Antiquity 23(4):467-489.

Warinner C and Tuross N. (2015) “Ancient DNA and Stable Isotope Analysis of the Teposcolula Grand Plaza Cemetery,” in Nelly Robles-García, ed. Yucundaa: La ciudad mixteca Yucundaa-Pueblo Viejo de Teposcolula y su transformación prehispánica-colonial. Vol. 2. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Tuross N, Warinner C, and Robles Garcia N. (2015) “Evidence for Mixtec/Dominican Interaction from the Radiocarbon Dates at Yucundaa (Pueblo Viejo de Teposcolula),” in Nelly Robles-García, ed. Yucundaa: La ciudad mixteca Yucundaa-Pueblo Viejo de Teposcolula y su transformación prehispánica-colonial. Vol. 2. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Blog Posts

Behind the paper: Mixtecs, Aztecs, and the great cocoliztli epidemic of AD1545-1550. Nature Ecology and Evolution blog, February 7, 2018.

Learn More

Conquistador contagion, Archaeology Magazine, 2018