Medieval Pigments and Women Scribes in Germany

Before the fifteenth century, scribes seldom signed their works, raising questions as to the identity of early scribes and illuminators. It has long been assumed that monks, rather than nuns, were the primary producers of books throughout the Middle Ages, but recent historical research is challenging this view, revealing that religious women were not only literate, but also prolific producers and consumers of books.

The vast majority of illuminated manuscripts surviving from the medieval period was produced by anonymous scribes. Who were these dedicated copyists and painters? Recent research by historian Alison Beach and others has found that many of these anonymous scribes were in fact women. Following a trail of letters, marginal notes, handwriting comparisons, and other clues, more than 4,000 books from medieval Germany have now been attributed to women scribes.

Taking this a step further, we have begun investigating medieval cemeteries using optical, elemental, and spectrographic techniques to identify scribes by the pigments embedded in their dental calculus.

Combining historical research with archaeological science, we aim to illuminate the lives of the women who quietly produced the books of medieval Europe.

Related Publications

Radini A, Tromp M, Beach A, Tong E, Speller C, McCormick M, Dudgeon JV, Collins MJ, Rühli F, Kröger R, Warinner C*. (2019) Medieval women’s early involvement in manuscript production suggested by lapis lazuli identification in dental calculus. Science Advances 5, eaau7126. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aau7126.

Radini A, Tromp M, Warinner C. We found lapis lazuli hidden in ancient teeth – revealing the forgotten role of women in medieval arts. The Conversation, January 11, 2019.

Warinner C, Beach A. Anonymous was a woman: Illumininating the writing and art of religious women in the Middle Ages. En Situ, Spring 2020.

Learn More

New York Times: “In an Ancient Nun’s Teeth, Blue Paint — and Clues to Medieval Publishing,” by Steph Yin, January 9, 2019.

New York Times: “In an Ancient Nun’s Teeth, Blue Paint — and Clues to Medieval Publishing,” by Steph Yin, January 9, 2019.

The Atlantic: “Why a Medieval Woman Had Lapis Lazuli Hidden in Her Teeth,” by Sarah Zhang, January 9, 2019.

National Geographic: “Female medieval master artist revealed by dental calculus,” by Andrew Curry, January 9, 2019.

Scivitas by Hildegaard von Bingen, 12th century manuscript produced in Germany, Heidelberg University Library. Earliest confirmed use of lapis lazuli pigment in a manuscript attributed to a woman scribe in Germany.

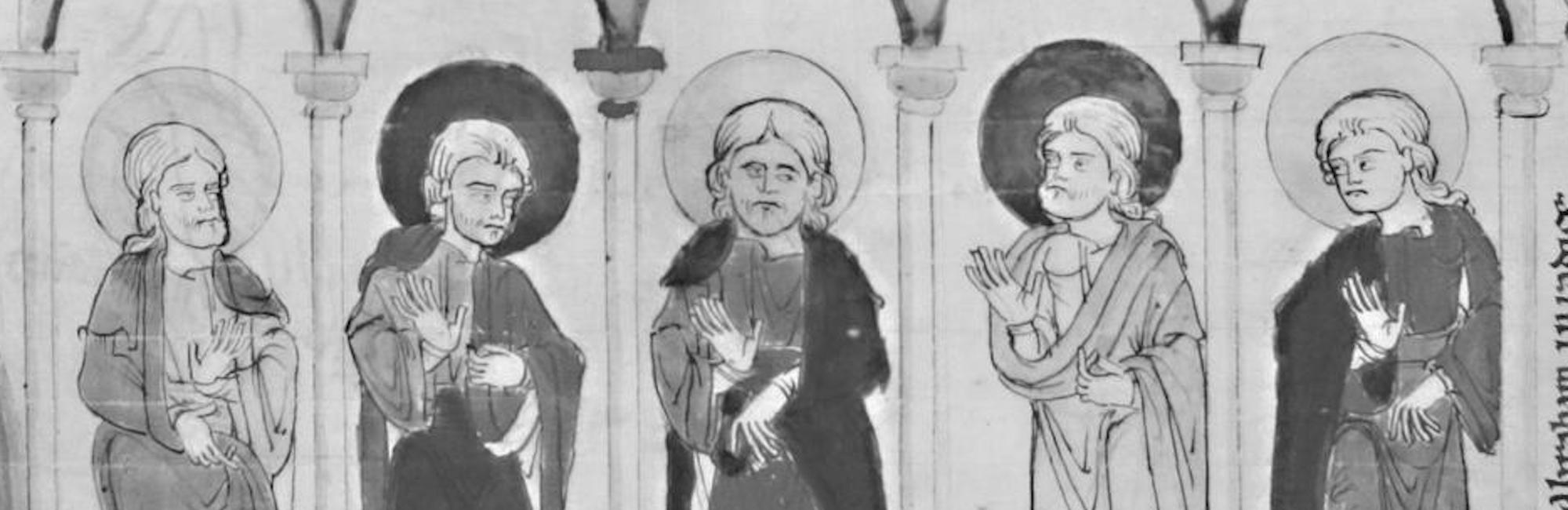

The Homiliary of Saint Bartholomew, by Guda, 12th century manuscript produced in Germany, Frankfurt am Main University Library. Contains the earliest known self portrait of a medieval woman scribe.

The Homiliary of Saint Bartholomew, by Guda, 12th century manuscript produced in Germany, Frankfurt am Main University Library. Contains the earliest known self portrait of a medieval woman scribe.

Beatus Apocalypse of Genoa, 10th century manuscript produced in Spain, illustrated by the priest Emeterius and Ende, a “woman and servant of God.” Earliest known medieval manuscript painted by a woman.

Codex Gisle by Gisela von Kerssenbrock, ca. AD 1300 manuscript produced in Germany, Osnabrück diocese archives. Deluxe manuscript containing lavish use of gold and other expensive pigments. The illuminated nativity scene depicts a self portrait of choirmistress Gisela and fellow nuns singing in a choir.

Diemut of Wessobrunn, a prolific 12th century female scribe and illuminator who produced an astounding 45 books during her lifetime at the Wessobrunn monastery.